Solidly located in Western Asia and sharing borders Russia and Iran, Baku, Azerbaijan does not initially sound like a dream tourist destination. Here’s what to do in Baku, what I wish I knew before arriving, and what to avoid in Baku.

Table of Contents

Baku is what might happen if Istanbul and Singapore had a baby.

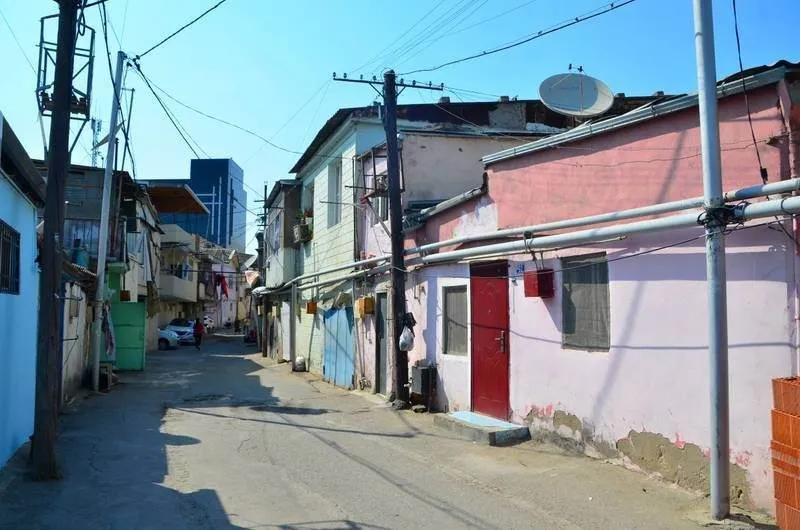

It’s not as large as Istanbul (15 million) or Singapore (5.6 million), but Baku’s 2.2 million residents live in a city where chaos meets order head-on. One minute you’re walking on a wide sidewalk, using surprisingly well-appointed underground pedestrian walkways, the next you’re on a street where a block of cars are all double-parked and traffic is at a standstill as a result. Construction changes more than a few patterns, and roads / areas that seem well-built for loads of traffic barely have any.

Things are changing. Fast.

This post is a snapshot of a fast-moving city, written in June 2019 based on a week-long visit in the same month.

The version of Baku in a European Economic and Business report from 2003 is almost unrecognizable, compared to the Baku seen today. Since 2013, an online e-visa system has replaced the previous system which required a letter of invitation “approved by the Azeri Ministry of Foreign Affairs”. That e-visa is required for citizens of close to 100 countries, with former Soviet states mostly exempt from needing visas.

To be sure, that system only allows up to a 30 day tourist visa, and if you stay more than 15 days, you’ll need to register with the government. SIM cards got a lot easier to get in 2016, though you’ll want to go to an official store to avoid paying inflated ‘gray-market’ prices. We went to Bakcell’s official store in the walkable cosmopolitan area, nearest to Sahil metro station.

Tourism nearly doubled from 2008 to 2017, with most tourists being from neighboring countries like Georgia, Russia, Iran, and Turkey. Wikipedia notes some 12,291 US tourists came to Azerbaijan in 2017, or some 0.044% of all tourists — essentially a rounding error.

The city’s long history is not on display.

(I wish I knew more of the context behind this mosaic. If it looks like an awkward angle, it’s because it is — there’s only a few meters worth of alleyway between this wall and the building next to it. No easy way to see more of it, either.)

Baku is probably best known for two things: oil and winds. Petroleum has been known about in the area since at least the 8th century, first drilled for in 1846, and in the early 20th century, half the oil sold internationally in the world came from Baku. The Soviet Union invaded a couple of years after World War I ended, and the city was of strategic importance during World War II.

After the Soviet Union fell in 1991, the city seems to have had the money to rebuild itself on a grand, dramatic scale. It’s fair to say the city has been invented and re-invented as time has gone on. Some grand-looking skyscrapers make up the city skyline, but this also means areas like the Old Town have very little that’s authentically ‘old’.

The winds, remain, however — thank the city’s proximity to the Caspian Sea for that. These are genuinely brisk winds at times, so watch your hats!

Some parts are quite modern…

I have to give kudos where they’re due. There are a lot of gorgeous buildings and architecture in the city, and you’ll spot quite a few of them on your way to or from the airport. The trio of Flame Towers in western Baku are a night-time highlight, and the waterside park / natural area is a fine place to bike, walk, or just relax.

Another modern sight worth noting: the eggplant-purple London-style taxis, imported by the thousands from London in 2011 with the color hand-chosen by the president himself.

…but there’s a darker reason behind that.

I first learned the term ‘caviar diplomacy‘ while researching our stay in the country. Essentially expensive gifts to selected non-Azerbaijanis for their cooperation — or silence — in some matters, this piece from 1843 Magazine (part of The Economist‘s family of publications) is a worthy longform read. If it’s making Baku or Azerbaijan look good, or avoiding valid criticisms of an autocratic country, someone’s probably received a bribe to do so.

The country has put on the Eurovision Song Contest in 2012, the European Games in 2015, and annual Formula 1 (F1) races since 2016. Events tied to Europe and the wider world have had a single aim: to make the Azerbaijan regime look good and to distract from the crackdowns, arrests, ballot-stuffing, and censorship of that regime. The F1 grandstands and garages standing in front of the House of Government (which are likely to remain in place for the next F1 event in 2020).

You as a tourist aren’t likely to see any of that political apparatus, of course, and that’s by design. The more carefully that stuff is hidden, the more you can awe at the pretty buildings.

The city is Eastern-European-like cheap…

Well, the parts that aren’t selling Jimmy Choo shoes, at least. Food at grocery stores, tourist attraction prices, and so on are on par with other capitals in Eastern Europe.

…but the tourism industry has a long way to go.

Dual-pricing exists — can’t say I’m a fan, but it’s rarely more than a couple of manat, so it’s not too much to worry about. With a higher admission for foreigners comes higher expectations, however — or at least, expectations of having multiple languages to put exhibits into context.

The most mystifying element, personally, was being asked for our names and phone numbers at almost every museum we tried to enter. ‘Why do you need this?’, I asked. ‘It’s for the system’ came the reply. ‘Why does the system need it?’ was responded to with a smile and a shrug. They didn’t know, didn’t care, and were just following orders. No one’s actually checking these against any sort of ID, however, so use a fake name and give a fake number if you want.

Getting around is best done by taxi app.

Bolt (formerly Taxify) is the app you want, to be specific. Hail a taxi, mark your location, pay the driver in cash when you arrive.

Yes, there’s an extensive network of city buses and multiple lines of subways to connect the city, and Google Maps is your friend on getting around the city. Rides are generally 30 qapik (there are 100 qapik are in a manat, like cents in a dollar) or about $0.18 USD.

What to see?

The Atashgah Fire Temple was easily the highlight of the trip. While a bit out of town, it’s accessible by public transportation (bring coins for the buses – as of June 2019, the white buses don’t have card readers). It’s one of the only actually-looks-and-feels old touristy destinations in the city. It’s 4 manat to get in (half that for locals), and while reconstructed, it’s a decent look at a Hindu, Sikh, and Zoroastrian place of worship from long ago.

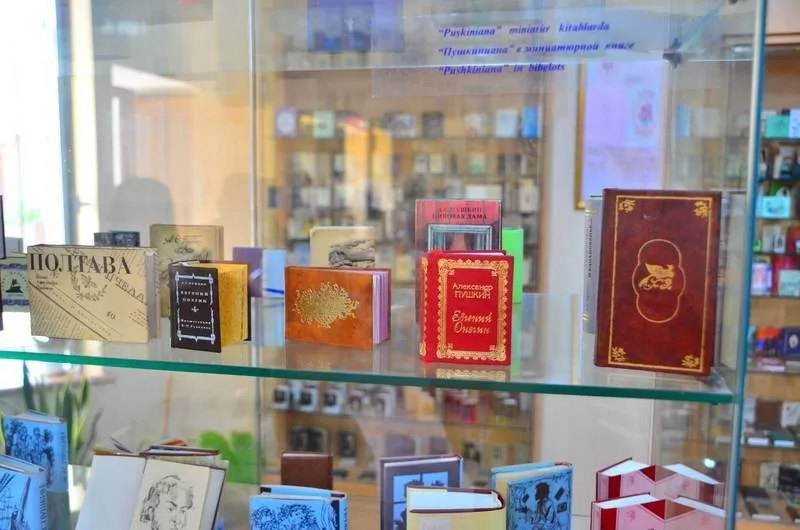

Another highlight is the Miniature Book Museum inside Baku’s Old Town, a stone’s throw from the Icharishahar metro station. Beyond being free to enter, the collection has earned a Guinness World Record in 2014 for having the largest collection of miniature books. It’s an eclectic, international collection where you’ll recognize at least a few titles, no matter your nationality or interests.

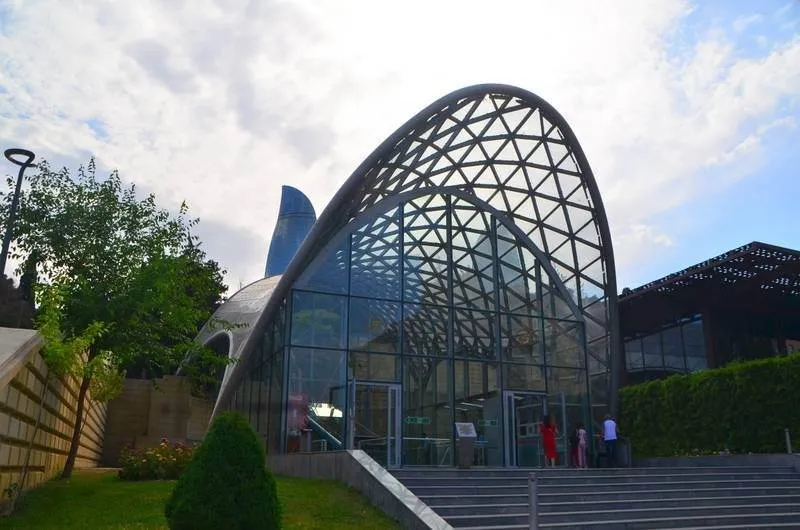

We visited the site of the Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre — a gorgeous, curvaceous building designed by the world-famous architect Zaha Hadid — mainly to awe at the building. It’s genuinely a gorgeous building, though we passed on paying a relatively expensive admission fee to hear propaganda stories of the former dictatorial, authoritarian president. Don’t worry, though, there’s lots of colorful bunnies and snails (?!?) to get pictures with:

As already mentioned, the Flame Towers should be a nighttime visit. While you can easily walk the sidewalks nearby, you don’t need to be exceptionally close to enjoy the light show.

We also walked through the so-called Old Town, which feels so newly reconstructed it feels laughable to call it ‘Old’. The Maiden Tower is worth a quick picture, though it’s not an area we hung around for long as it’s ground zero for the touts and the tourists willing to pay 15 manat ($8.80 USD) to enter.

A modern funicular costs 1 manat to cover a hilly area. It’s a decent ride, but nothing special — and despite the modern design, basic things like a ticket booth and signs are missing.

What to avoid?

I passed on the Azerbaijan Carpet Museum upon learning the cost for taking pictures (10 manat) is more than the cost of admission (7 manat). ‘Why is that?’ I asked. ‘You can print the patterns… like in a journal’ came the nonsensical answer. You could take pictures with your smartphone, though. Get a picture of the building, which looks like a rolled-up carpet, then move on.

The Independence Museum of Azerbaijan (now inside a building called ‘The Museum Center’) is easy enough to find, and the authoritative building dates from the Soviet era. (It was originally the Baku branch of a Lenin museum, though you’ll only learn that on their website.) Once you’ve accepted their need for a name and phone number, the dual pricing, and the surreal levels of propaganda, you get in and realize there’s just not a lot here. The few actual exhibits are surrounded by copies of untranslated text, and while some exhibits have decent explanations in three languages, most lack any knowledge or context beyond what’s on a Wikipedia page.

An English-speaking guide (minder?) appeared out of nowhere a few minutes after we arrived — I’ll give her full marks for effort, but I literally couldn’t understand more than one word in four despite being in a quiet room with nothing else going on. The same building holds a separate museum of music culture, and costs 1 manat ($0.59 USD) to enter. After finding the correct open door, we enter to find this:

That’s basically how it continued — presumably authentic instruments, kept in glass cases, with nothing more than the local name for that instrument. In halting English, one of the workers started trying to sell me a DVD or CD of some type. After a few rooms of this, including one of foreign instruments, I run into a group of musicians practicing and concluded that’s the end of the museum… Whatever the admission fee may be, having little in the way of explanation is inexcusable.

We also read about the world’s tallest flagpole being in Baku (perhaps another way of garnering attention in a extravagantly useless way), and of course had to check that out. It turns out the site is now closed to the public and there is no flag or flagpole:

Yes, there was a flag that measured 70 meters long and 35 meters long (your standard-issue hang-outside-your-house flag is usually 1.5 meters by 0.91 meters). The flagpole was 162 meters tall and weighed 220 tons. After much pomp and circumstance during its installation in September 2010, the flag had to come down a day later because of the wind. A $24 million US project is now an eerily quiet site that sits empty and cordoned off. (If it were to be reinstalled, it would now be only the third-tallest flagpole, thanks to other countries that also have more money than common sense.)

Conclusion

I definitely got the sense a kleptocracy was running things more often than not, mainly just from throwing money at problems to make them go away. The powers-that-be in Baku seem to care so much about its image that substance barely seems to matter. I can’t help but wonder what will happen 10 or 15 years from now, when the once-gleaming buildings desperately need upkeep and the world has moved on from fossil fuels.

Is it worthy to visit as a tourist? As with all things, it depends what you’re interested in seeing. The architecture is great, and there are standout destinations — be aware that things change quickly, and what was true today may not be true tomorrow.

Have you been to Baku? Comments are open.