Changi Prison was originally built by the British, who ruled Singapore at the time, in 1936 for civilian prisoners. After the city fell to the Japanese in 1942, the prison was used for several thousand civilian prisoners of theirs while POWs from Allied nations were kept in the nearby Selarang Barracks. Over time, the name Changi Prison came to be used to refer to both. The prison remained in use after the conclusion of the war and was finally demolished in 2000 to make way for a new consolidated prison.

A quick note: this guest post comes to you from my awesome wife Laura, who came with me to Singapore during my recent conference. She got to explore a bit while I was stuck indoors for most of two days — the horror! If you’re in need of a Korean-to-English translator or French-to-English translator, look no further.

Changi Museum (AKA Changi Chapel and Museum) was built to commemorate those who lived and died in Singapore in WWII and, in particular, those who were imprisoned in the old Changi Prison at that time under severe conditions. It’s a small building packed full of history and stories both terrible and inspiring.

Please note that as no photography is allowed inside the museum, most of the pictures here are from the Changi Museum website and included to illustrate my story. The website itself has a lengthier description and promises a “virtual tour” by the end of 2014.

The first part of the museum consists of a series of displays on either wall. Generally, the story is told in the middle and there are relevant items to either side — notebooks, belongings of POWs, that kind of thing. This is fantastic if you really want to read in-depth about the history of the place and what went on there. I am very interested in such stories, but found these literal walls of text to be a bit too much for me (I am much more fascinated by actual items, which help me feel like I can get closer to the events). There was also a series of boards in the centre with the history of WWI, I assume because of the centennial; however, as the prison hadn’t even been built at that time, they didn’t seem very relevant.

All in all, I found this section of the museum to be very well done but a little too densely packed with information. However, I appreciated all the quotes and stories from survivors.

The very end corner of this first section was the most interesting part of the museum to me. The dimensions of an actual jail cell were painted on the floor:

So you could really get a better sense of what the living conditions were like. The stories also veered more toward the personal, with descriptions of camp life and how people coped and made do with very little in some very fascinating ways. For example, one POW wrote and illustrated (and very well, I might add) a children’s book for the children in the camp just from materials around the camp. The cover of this book was on display. There was also a recipe book with camp recipes combining the rather poor camp rations in different ways to make the food better.

The quilt hanging on the wall next to the painted jail cell was quite touching. Women and men were housed separately in the camp and people had no way of knowing if their spouses were even still alive other than gossip passed under various pretenses, so when the women in the camp were made to quilt these quilts to keep the men warm, each woman made a square with her name in it so that when the quilt reached the men, her husband could know that she was still alive.

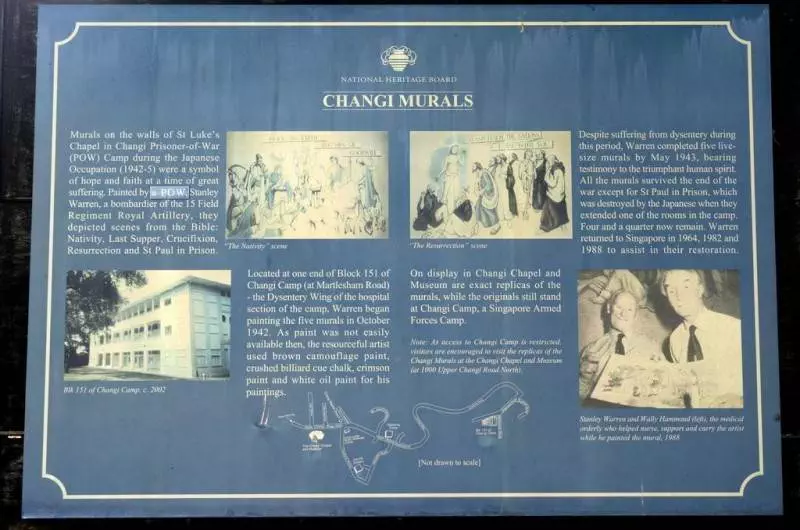

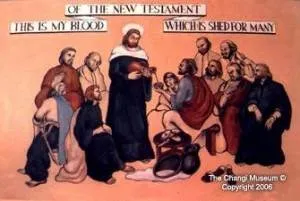

The next section was a replica of the old chapel. The murals in the chapel are justifiably famous, as indicated by a plaque at the entrance to the museum:

They were done by a prisoner who was, again, using only the materials to hand and making paint in creative ways to get the colours he wanted if they weren’t available.

Finally, there was also a replica of the stage (the “Kokonut Grove”) made by the prisoners for the plays they put on; a quote from a prisoner in one display mentions how he didn’t see the point in living on past the end of the war if only his body was alive and his mind wasn’t, so the prisoners tried in various ways to keep their minds active — there was even a “university” where prisoners gave lectures on whatever subject they happened to have knowledge of.

As you leave (or arrive; the museum is arranged so the entrance and exit doors oppose each other), there is a small open-air chapel with a little altar. You can leave a message here if you wish.

Name: Changi War Museum / Changi Prison Museum

Address: 1000 Upper Changi Road North (GPS: 1.362174, 103.973998)

Directions: Take the MRT to Tanah Merah (EW4), then get on bus 2. You can also go to MRT Tampines (EW2) and then get on bus 29. Either way, get off at the Upper Changi Road North bus stop and cross the street to reach the museum.

Hours: 9:30am-5pm (last admission at 4:30pm)

Admission: free

Phone: (65) 6214 2451

Website: http://www.changimuseum.sg/