During our epic three-month Europe trip, Laura and I took a few days to explore places separately. Reading this guest post by my wife made me wish we had seen this one together! Enjoy this look at a lesser-traveled former Nazi camp in southern France.

I’ve read pretty extensively about the Nazis and WWII. It’s a topic of great interest to me, and I’ve visited a few related memorial sites around Europe. However, as I was reading up for my trip through southern France, I discovered one I’d never heard of — Camp des Milles. It didn’t hold the same kinds of horrors as, say, Auschwitz or Oradour-sur-Glane, but it was still a place of considerable misery, a part of a lesser-known but compelling part of Nazi history. It also gave me a startling insight into perhaps one big reason why Europe is so reluctant to turn away the migrants entering it today.

The building itself has spent most of its life as a tile factory. It was built toward the end of the 19th century, and wasn’t a great place to be even then — workers had to carry heavy loads in often difficult conditions, including terrible winter weather. The factory had fallen into disuse by the beginning of the Second World War, and the French government of the time thought it a convenient place to house those considered enemies — Germans. Many of the Germans housed there were in fact anti-fascists, themselves persecuted by the Nazis.

Later, after the Nazis occupied France, they used the camp to house their own so-called “undesirables” — Jews and others they didn’t want around. The people at this camp actually had the chance to leave Europe, assuming they could get visas for elsewhere, but that was an incredibly complicated process as they theoretically couldn’t get a visa until they had a ticket to their new country, but couldn’t get a ticket to their new country until they had a visa.

Another problem was that many “safe” countries, including the US, simply didn’t want a flood of refugees on their doorstep and didn’t hand out a lot of visas. There were a number of relief organizations that helped people get out of France despite the ridiculous bureaucracy involved, so some of those housed at Camp des Milles were able to eventually leave. Many, however, could not, and over 2,000 were eventually deported, mainly to Auschwitz. The museum actually blames this on the French Vichy government, not the Nazis — it was apparently something the government did to help them out, not something the Nazis made them do.

The visit starts with a trip through the museum which explains the history of the camp and the problems faced by its residents. Later, you head into the part of the factory that was actually used for internment. It was never really converted from its original form, so people just slept in parts of the old warehouse and kilns. It was dark, uncomfortable and generally pretty miserable. To make matters worse, there weren’t nearly enough toilets to go around. Different groups would take up different areas — for example, the Legionnaires, below.

After walking through this part, you head up into another part of the warehouse. After the war, the tile factory reverted to its original purpose and actually continued producing tiles throughout the twentieth century. (The museum/camp itself was only opened for tourists in 2012 — perhaps one reason I’d never heard of it.)

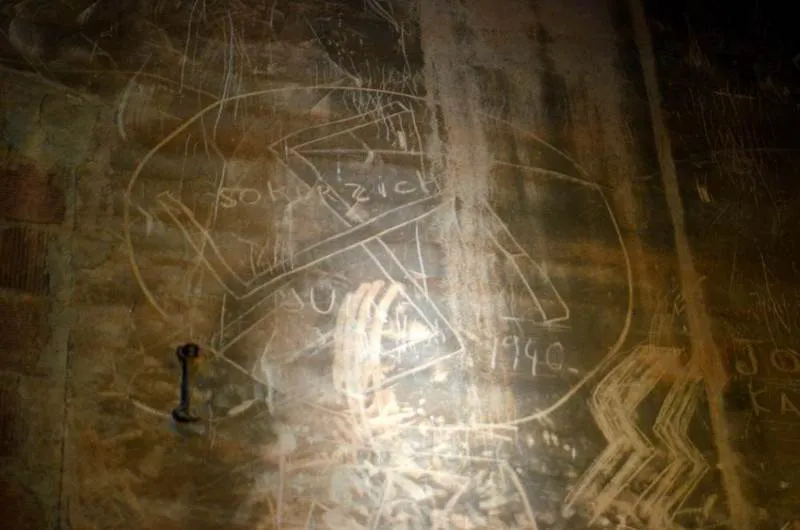

One notable feature here is the swastika carved into the wall. The signs explain that this is fairly recent, not from that period of the camp’s history, and a good example of why we still need to fight against racism and intolerance. I thought that was a nice way of putting awful graffiti to good use.

You end up in another exhibit which examines the reasons all this was able to happen. The primary culprit seems to have been conformity — people don’t want to go against the group, so they go along with terrible things. The museum exhorts us to think about the consequences of what we do. One prominent poster shows a group of people at a Nazi rally giving the Heil Hitler salute, with just one man crossing his arms and refusing, as it was the people who refused to go along with the Nazis who ended up being the real heroes of the time.

Continuing on, there’s the old dining house. One notable aspect of Camp des Milles is that many of those interned there were artists and writers. Some of their art is even left over on the walls of the camp, and you can see it when you walk through.

The dining house is a particularly good example, with large (and funny!) murals painted by the internees commenting on their situation. The first picture below shows a group of people of different nationalities:

The caption on the second reads, “Maybe our drawings can soothe your appetite”:

There are sometimes temporary exhibits. The one on display when I was there was about Jewish children deported to Auschwitz from various towns in France and included names, pictures and brief biographies. This part of the camp was very difficult to see and, to be honest, I ended up rushing through it a bit.

The camp is located a short bus ride out of Aix-en-Provence, itself a short train ride from Marseille. It’s very easy to get to using public transport.

Name: Site-Mémorial du Camp des Milles

Address: 40, chemin de la Badesse, 13547 Aix-en-Provence, France (GPS: 43.503393, 5.382985)

Directions: From the Aix-en-Provence train station (gare), walk roughly northeast to Avenue Victor Hugo and look for the stop for bus #4. Take bus #4 (you can buy a ticket on the bus) and get off at Gare des Milles. From there, it’s hard to miss — just look for the large brick building surrounded by wire fences.

Hours: Open daily 10 AM-7 PM (ticket office closes at 6 PM) except Jan. 1st, May 1st and Dec. 31st

Admission: €9.50 (full price), €7.50 (reduced)

Phone: +33 (0) 4 42 39 17 11

Website: http://www.campdesmilles.org/index.html